By Casey Wandasan

I have always had an interest in the natural sciences and anything non-fiction. As a kid, I used to be obsessed with dinosaur shows and prehistoric life. If you had asked me while I was in elementary school what I wanted to do for a career, I would have said “paleontologist!” As I grew older in my late teen years, my interest narrowed. The first club I joined was the math team at my local high school. Math turned from a subject I was good at into one I was great at and would actively do for fun in my free time for years to come. However, I knew I did not want to be a mathematician; I wanted science to be involved. So, I thought about being a physicist by the time I graduated.

I double majored in physics and mathematics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa; however, I began to feel off about it. I felt lost and confused, without a purpose. Do I really like pure physics? What would I specialize in? Attending university expanded my horizons by exposing me to various subjects I would never have thought to be interesting, including chemistry, which I would say is one of my favorite subjects in addition to physics and math. Ultimately, I ended up changing majors to Earth Sciences (formerly Geology and Geophysics) at the beginning of the spring semester of 2022. My new career goals are in geophysics. Geophysics studies the earth from a physics perspective, yet it has deeply rooted connections to other geosciences. In other words, geophysics incorporates most of my interests.

My current major, Earth Sciences, feels right and aligns with my overall passion. I got to learn about rocks, earth processes, geologic time, geophysics, geochemistry, and prehistoric life. It made me have a deeper appreciation for all sorts of science, and it makes me wish I could learn all of it one day. I have met numerous amazing faculty members in the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) including Helen Janiszewski, a seismologist with whom I am doing research with and the person who recommended me to participate in this STEMSEAS experience. Thank you, Helen!

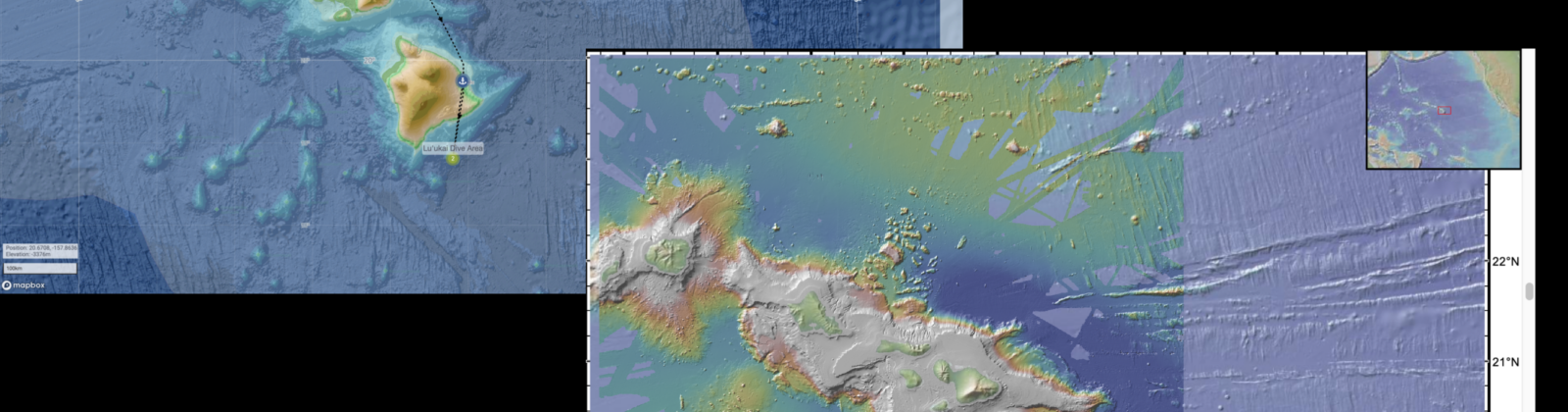

Screenshot from Helen Janiszewski

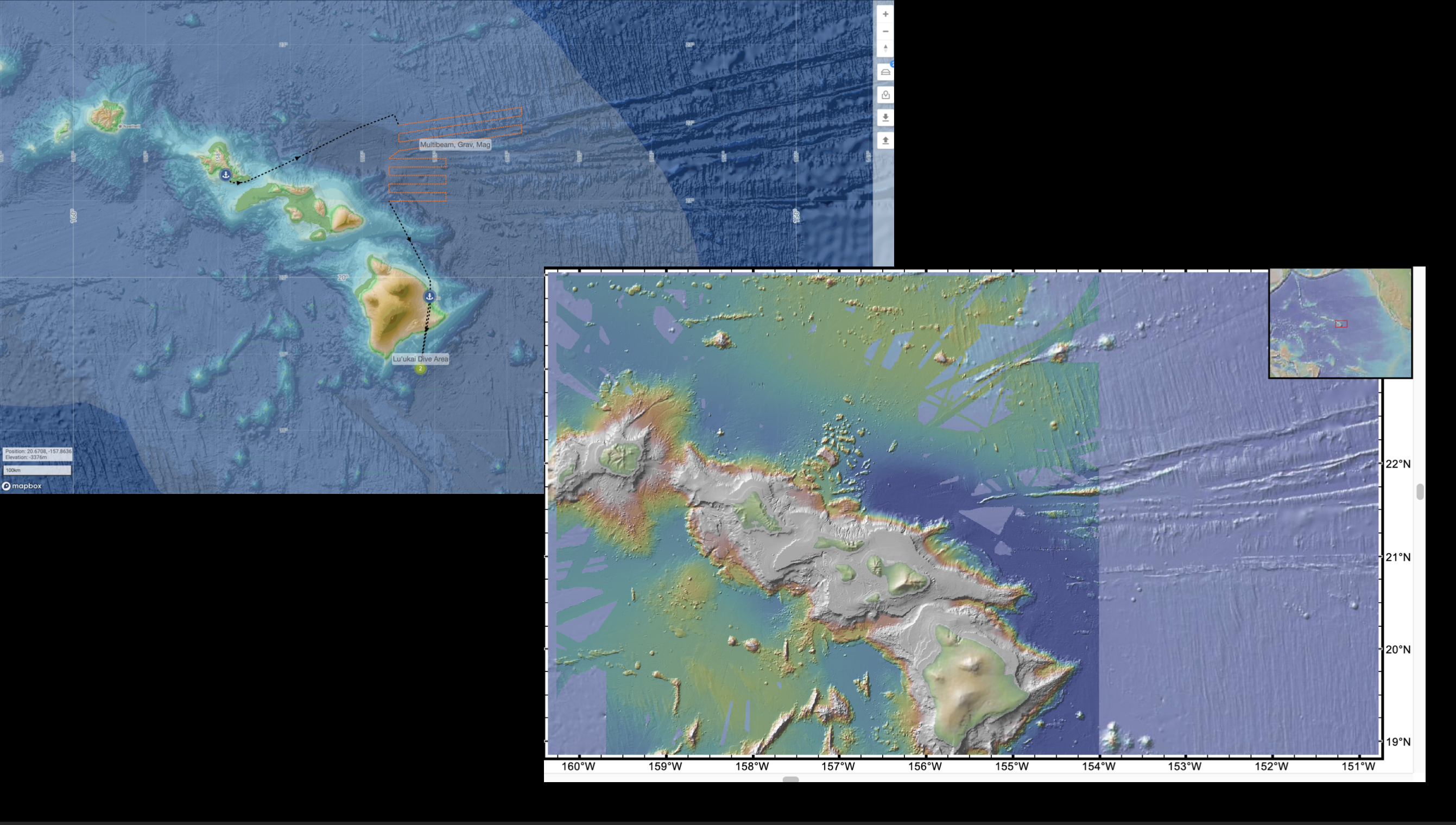

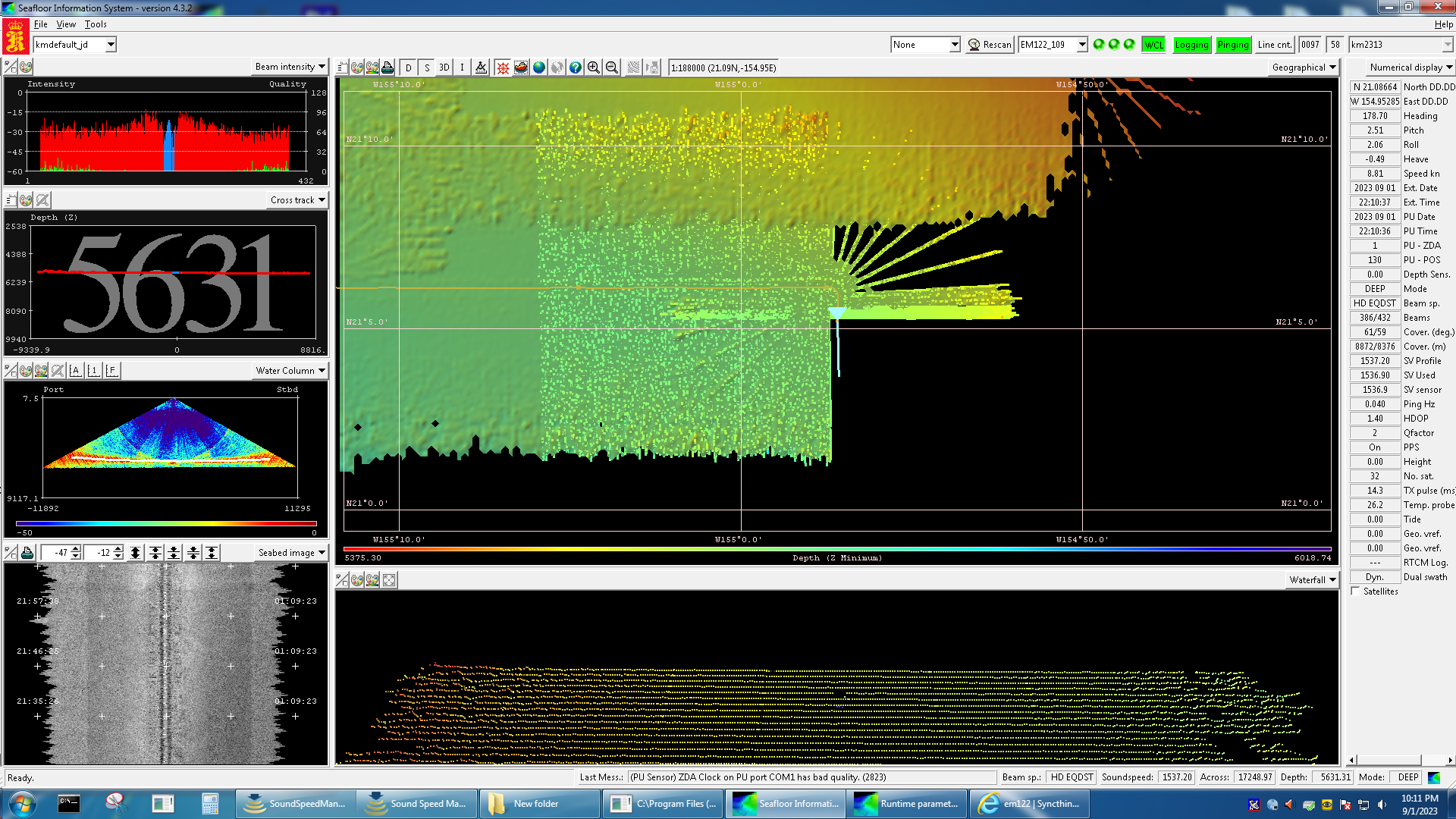

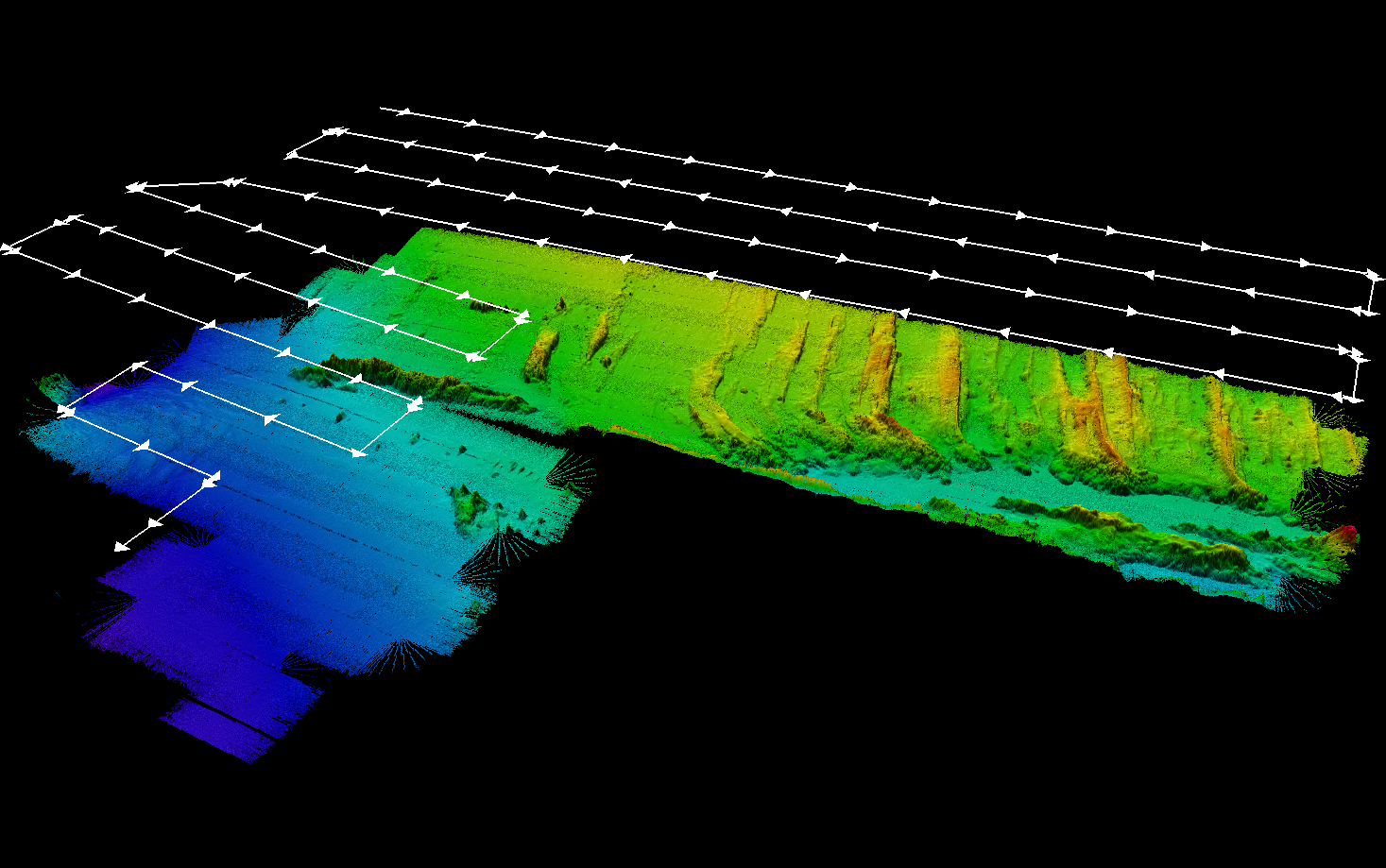

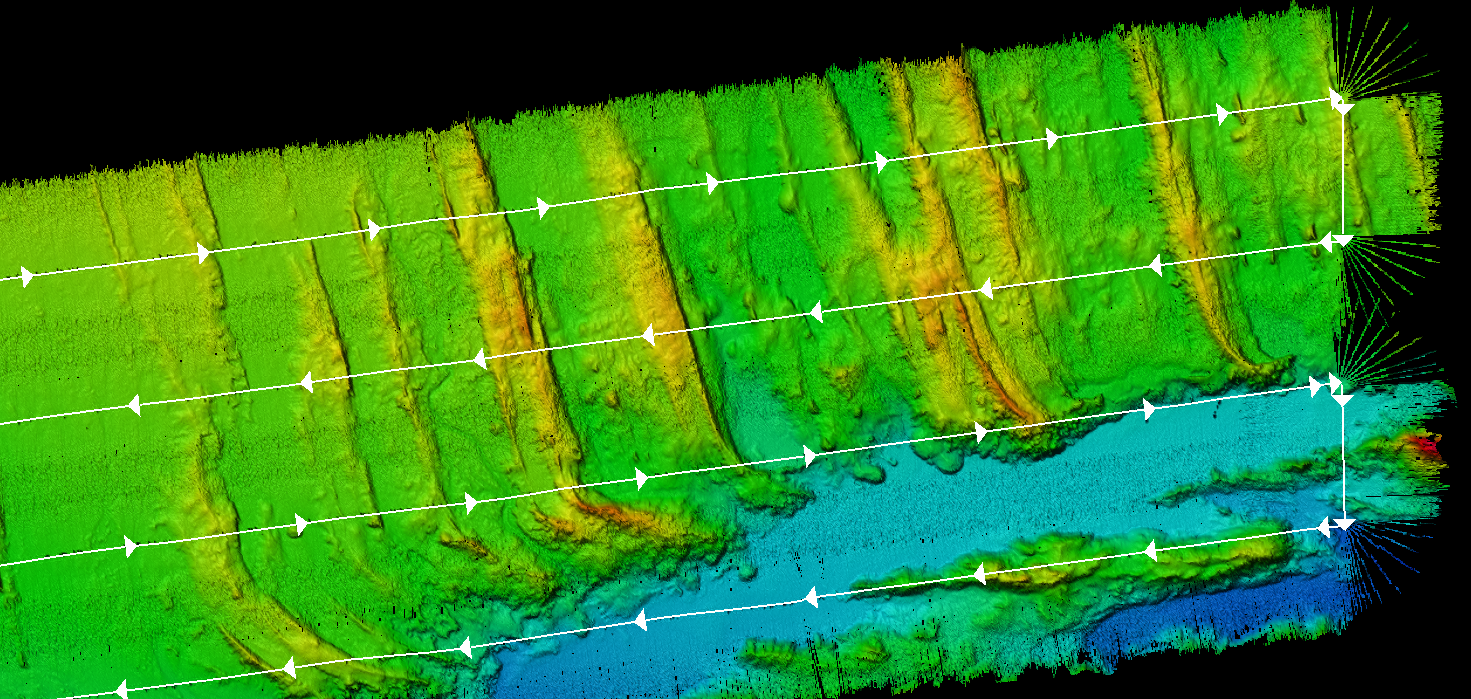

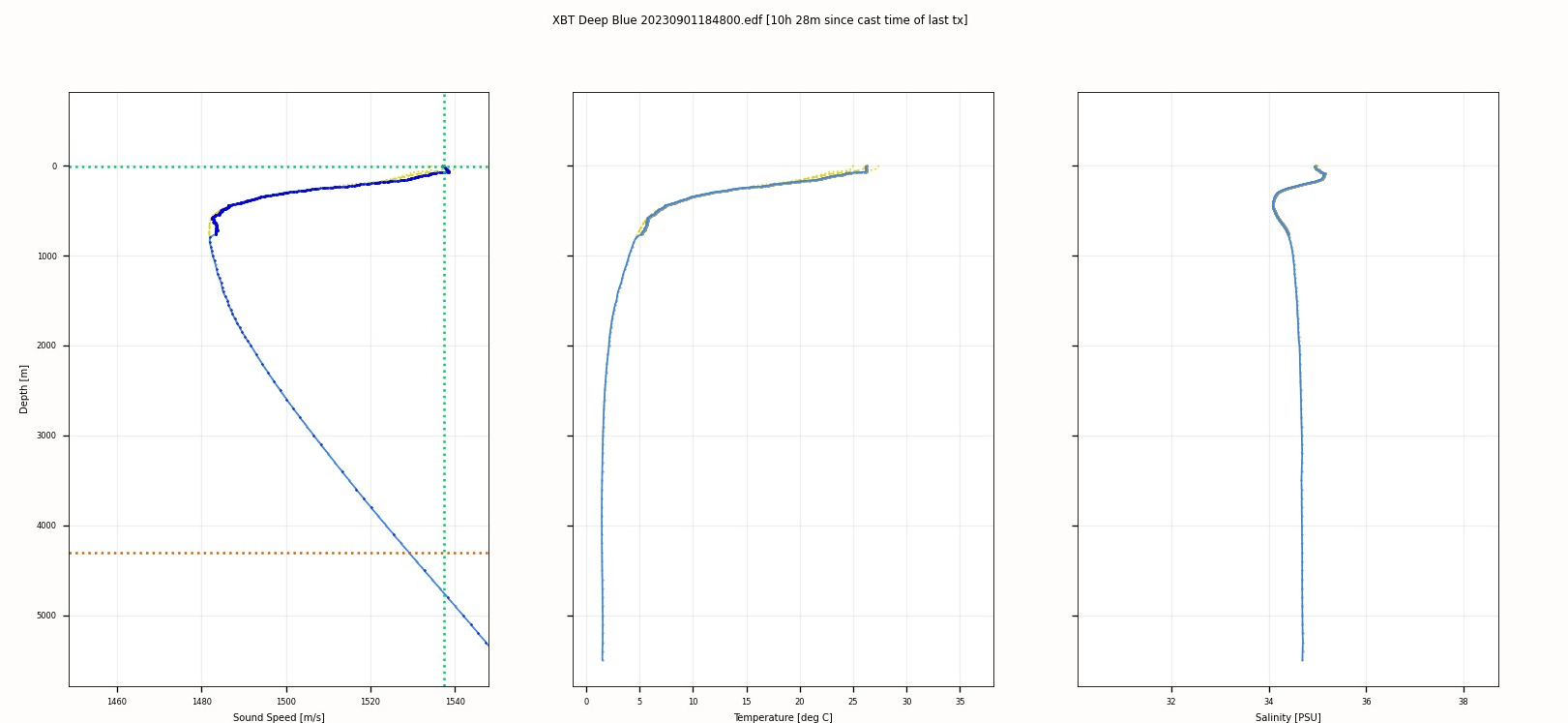

I am Testing the Waters with this STEMSEAS trip with the primary goal of learning about marine geophysics and deciding if it is something I want to do for a living. The trip is from Honolulu to Hilo on the R/V Kilo Moana and aims to map parts of the Molokai Fracture Zone, as shown in the map above. The ship maps the seafloor using a multibeam sonar, which sends several hundred equally spaced pings or sound waves from a transducer through the water column directly below the ship at angles 0–65° on both the port and starboard sides, perpendicular to the ship’s heading. These sound waves are reflected off the seafloor back to the ship, received by the transducer, and then logged, creating a swath of data. Multiple swaths are joined to create a 3D map of the seafloor. Note that values can only be calculated if we have a sound velocity profile, which can be determined by using an expendable bathythermograph (XBT). The Kilo Moana has different multibeam sonar systems onboard: a low frequency of 12 kHz is used to map deep waters, while a high frequency range of 40–70 kHz is used to map shallow depths less than 600–700 m.

Screenshot from Seafloor Information System (SIS)

Screenshot from Qimera

Screenshot from Sound Speed Manager

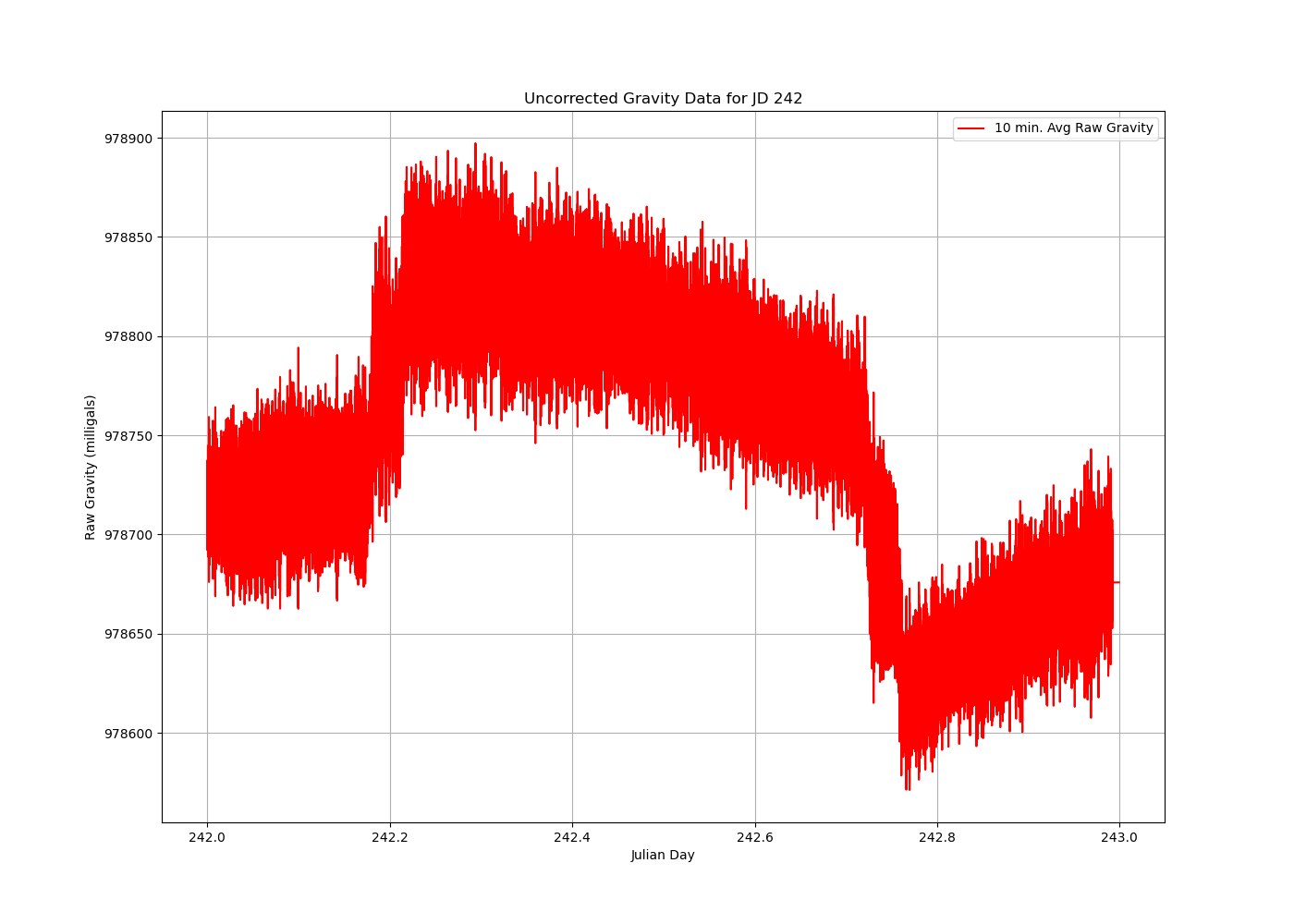

As for gravity data, there are two onboard gravimeters. One of the gravimeters is used to take land measurements, particularly at ports where gravity has been measured previously. The second is mounted and actively taking measurements at sea, locked in a secure room where no photos of it can be taken due to the International Traffic in Arms Regulation (ITAR). This gravimeter is secured in a box mounted with four legs, which reduce the shock from the ship’s rolling motion, and is on a gyro-stabilized platform within the box, which always levels the gravimeter. The device must always be powered, and if the ship loses power, there are backup batteries that should last 24 hours. Once the gravimeter loses power, it must be recalibrated, and this is considered a difficult and tedious procedure that the technicians want to avoid. They do weekly gravimeter tests, which I was able to participate in with one of the technicians. The maintenance check utilized a multimeter to determine if all systems were running at the proper voltages and was subsequently logged into a laptop. While these tests are being done, data collection will come to a halt.

MATLAB Plot from Daily Gravimeter Data

Another aspect of geophysics is magnetic data collected by a magnetometer dragged behind the ship ~150 m away. It is used to measure magnetic fields and determine magnetic anomalies, which could tell you information about the subsurface and rocks. Generally, the ship’s data, including the gravity and magnetic data, are saved into a public portal called Rolling Deck to Repository (R2R), which can be accessed by scientists.

Overall, the science involved on the Kilo Moana is very interesting and something I would not mind specializing in. The multibeam system and the plots that were produced are incredible. Now, I really want to learn the physics involved with transmitting sound waves. Gravity data is something I have used before and is not very surprising; however, now I want to know what kind of research can be done with this sort of data. The downside of research cruises is sea sickness or motion sickness. Almost every single day, there was a point in time when I did not feel good. I had to take Dramamine often, and the medication would make me feel drowsy. I have not had major incidents yet, so it can be manageable.

Thank you, STEMSEAS, for this opportunity, and thanks to the crew who satisfied my curiosity. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that helped me narrow down my career path.