[cross-posted at Mountain Beltway]

I had one of my students ask me this morning about what was the most interesting thing I’ve learned on this expedition. This is my first time going to sea out in the open ocean, out into the High Seas. All my previous time aboard oceangoing vessels was in the coastal waters of some landmass (Alaska’s Inside Passage, the Chiloé Archipelago of Chile, the Galápagos). Actually, come to think of it now that I list those out, they’re all eastern Pacific locations, more or less butted up against the western shores of the Americas. These locations are zones of oceanic upwelling, where cold, nutrient-rich waters from the deep ocean are tugged upward as winds blow surface waters offshore.

Those coastal waters are famously rich fisheries, a major “hunting ground” for marine protein to feed humans. But they are also the “hunting ground” of countless marine species, from great white sharks and turtles to whales and seals. And birds.

I’m a birder, so one of my side motivations in joining the STEMseas2YC transit cruise aboard the R/V Thompson was to see what sorts of birds I might encounter out in the way-offshore Pacific ocean.

Here’s what I saw yesterday:

In an hour of standing on deck and watching, I saw five individuals of one species: the Black-footed albatross.

On one level, that’s so super awesome it makes me squeal with glee – this is a “lifer” species for me, and I’m thrilled to see it, in a place where so, so few people get to go.

On the other hand: I saw five individuals of one species.

That’s it.

Five total birds.

I find this paucity of species quite striking. It’s as striking as the deep, vivid blue of the sea here, or the fact that in every direction we look, there’s nothing – no land, no ships, nothing but waves and water. Below me is five kilometers of ocean – and to a first approximation, it’s basically empty. It’s shockingly devoid of life.

Being a scientific research vessel, the R/V Thompson is equipped with a nifty flow-through seawater sampling system. Using this, we can easily pull off an aliquot of local seawater and then look at it under the microscope to see what sorts of plankton inhabit these waters. We have been surprised (and maybe a little disappointed) to see that the plankton too are quite sparse. Our procedure is to run seawater through an 80-micron sieve for half an hour, then look at the final few cubic centimeters of water and then search and search those drops for signs of life.

Here are a few I photographed:

A few copepods, some diatoms, a handful of spiky radiolarians — these were noted, but only after a dozen science professors spent an hour scouring the seawater samples in earnest. The water is pretty empty of all life, not just birds. It’s “oligotrophic” in oceanography-speak.

Without many nutrients, there’s not much plankton, and so there aren’t many fish, and so there’s not much for my beloved birds to eat. It’s sparse out here… and the albatrosses keep cruising and cruising…

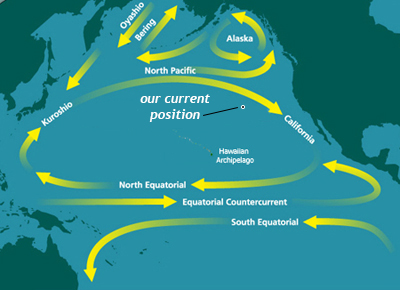

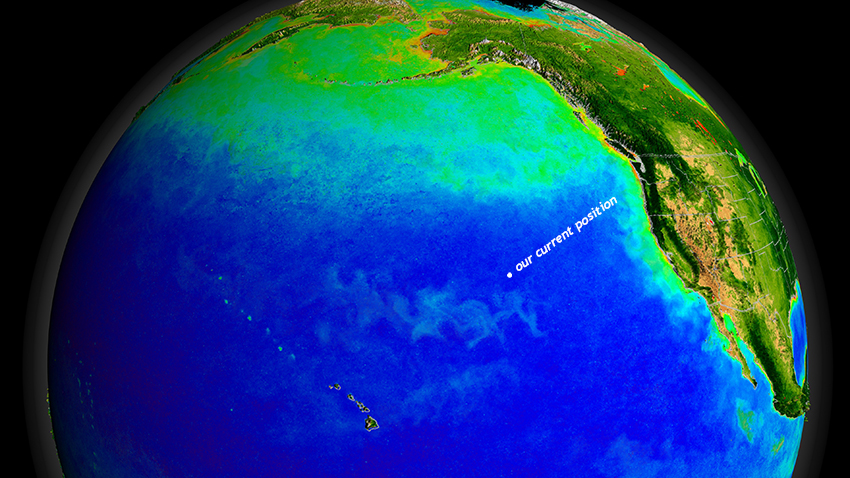

Here’s a NASA image showing primary productivity in the North Pacific, where warmer colors indicate more chlorophyll, and thus phytoplankton, the base of the flow of calories through the oceanic ecosystem, the food source for zooplankton and all the other heterotrophs (“eaters”) further up the food chain… Deep blue shows the absence of chlorophyll, and that’s where we are right now:

So, so much of the Pacific is a “marine desert,” lacking in nutrients and thus in life.

And the Thompson is out in the middle of all that nothing, motoring at 12½ knots day and night, through the near-boundless saltwater, eyes peeled for signs of life…

Callan Bentley