May 2, 2019

Today marks our fourth day aboard the R/V Neil Armstrong. The blue-grey sea has surrounded us for days, but in the main lab, six data displays help us qualify our current position on Earth. An underway display keeps track of our coordinates, as well as marking surrounding conditions such as water depth, air temperature, sea surface temperature, and wind direction. An adjacent lab display shows us our current route, updated live from the bridge. A pale blue background is intersected by a thin red line. A blinking target lies along it, with an opaque dot trailing slightly behind. That’s the Armstrong.

Zoom out, and our path so far becomes clear. Our origin, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, is located at coordinates 41.52*, -70.67*. Though we have been at sea for four days now, our latitude has only increased by slightly less than one degree north towards Reykjavik. Instead, we are jutting slightly into the Atlantic—heading steadfastly east.

In another map, the Armstrong’s planned route is overlaid against the bridge track—our current route as recorded by the bridge. As one might expect, we had initially planned to hug the North American coastline. We would have originally liked to travel northeast, in order to minimize the distance from Woods Hole to Western Iceland. So why the current route? The mantra, as I am beginning to grasp it, is that nothing at sea truly ever goes as planned.

On the bridge stairway, I call out to announce my arrival. I am stunned, as always, by the apparent serenity of this space. Compared to the ship’s jittery lower decks, the bridge is wide open, abundant with natural light and sea panoramas that help to settle my mild nausea. I’m here for ice watch. As the ship enters northern (potentially icy) waters, extra sets of eyes have been requested to assist looking out.

This brings me to our current trajectory. First mate Mike hands me today’s copy of the Iceberg Analysis report. On it, our corner of the North Atlantic is laid out in a grid of latitude and longitude. Numbers appear in a large cluster of grid squares, which refer to the number of icebergs reported within them. The ice cluster is marked with a clear perimeter, pointed to the south. Some squares house upwards of 30 cottage-sized icebergs. We’re avoiding those waters, coasting the report’s borderline.

Icebergs are easy to spot—they appear on radar for one, and their immense size allows lookouts to spot them on the horizon (approx. 8.5 miles) as they rise around Earth’s curvature. Student ice watchers aboard have been instructed to spot the smaller chunks of ice, “bergy bits” (car-sized) or “growlers” (smaller), which are still capable of causing damage. Although we’re out of the ice zone, I have already developed a heightened awareness of the report’s tendency to outdate itself. Captain let me know (casually) that the ice drifts south this time of year, and carries potential to cross our path. Ice breaks off and gets carried by the wind. Like anything else on the ocean—weather, currents, and other vessels—bergs are in constant motion.

I wanted the bridge to teach me about navigating the open ocean. From my first day aboard I asked to understand the many considerations of mariners who needed to route their path. What determined a ship’s speed? How do navigators predict what lies ahead? How often do they need to make decisions that are dependent on the future, and adjust their heading according to the influx of changes and obstructions the ocean brings?

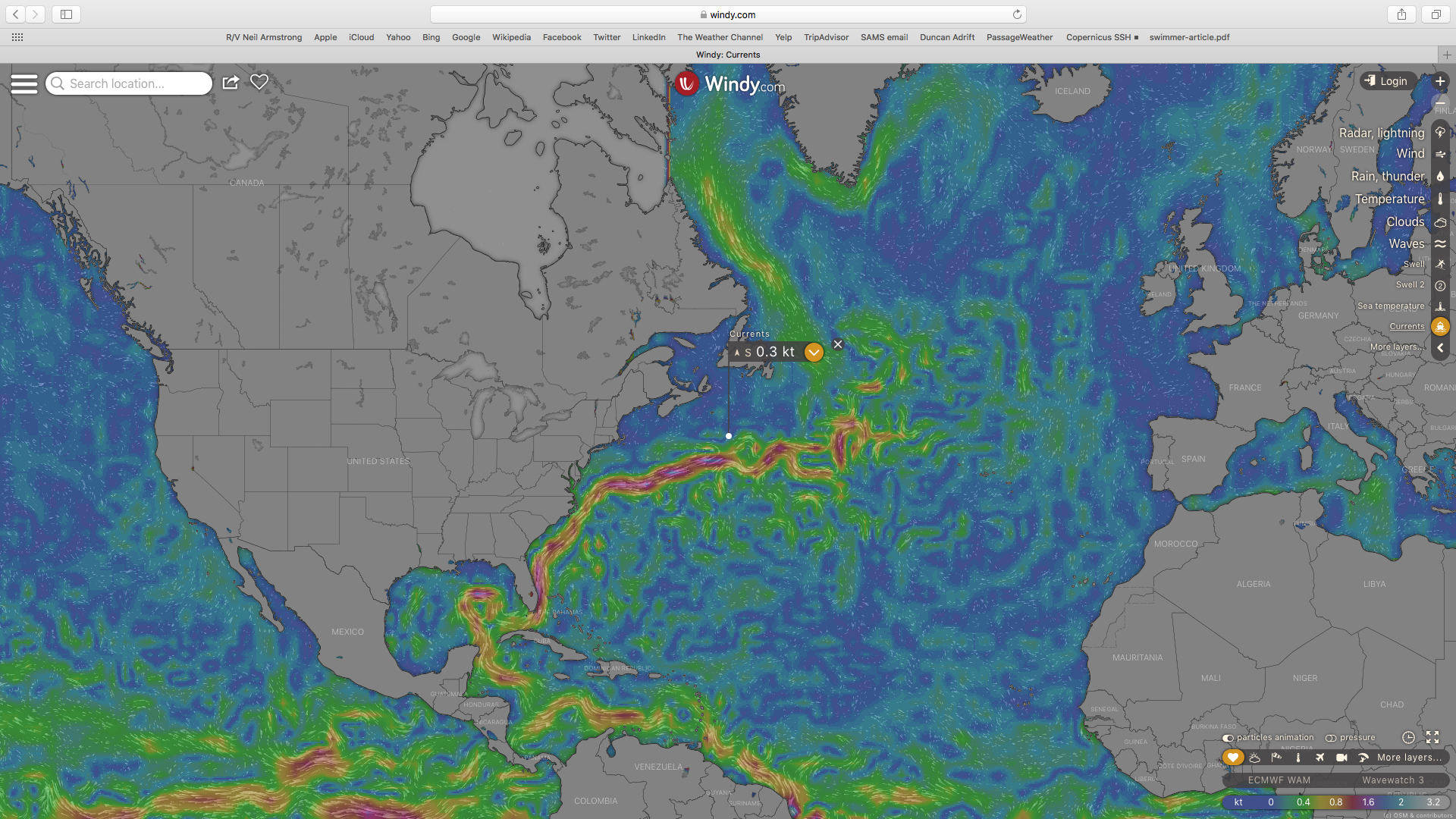

The working model of a ship on the ocean is dynamic. When the radar blinks with a distant object we can’t already see, we guess what it is based on speed (iceberg, ship?), and make passing adjustments accordingly. A layered map of currents shows our position in reference to the northernmost segment of the Gulf Stream, and we navigate its micro segmented eddies with hopes of being propelled forward. We make speed adjustments to travel ten knots through right whale protected waters (as they are known to be slow). We use predicting software to navigate our path through the weather we’re currently heading into, to avoid chances of southbound drifting ice.

This afternoon on ice watch, my eyes acclimated to detect the slight variations on the monotonous ocean plane after only a half hour or so. I watched whitecap after whitecap, waiting to find the one white gleam that didn’t go away. Through my binoculars, the horizon looked fuzzy instead of flat, with miniature swells of distant waves rising and falling. Dead ahead, the waves closest to us looked two-dimensional. Then from under the surface came a smooth plane that parted them. Darkest grey, a dorsal fin. It stayed there for a moment too long—I shouted out there was a whale—and we turned at the last second to avoid running into the creature. We were able to watch the whale linger on the surface for about twenty seconds until it passed behind, unharmed.

It was immediately identified it as a sperm whale. I’ve heard in stories circling around the Armstrong that it was considered to be a lucky sighting. I’ll take the good luck, the way that I’ve been taking conversations as lessons in navigation.

Our current coordinates, relative to surrounding ocean currents. Courtesy of Windy.com.

Michaela Robinson

Bard College Class of 2021